Sonification of register: Towards a new method for exploratory corpus analyses

By Roman Pfeifer (Folkwang Univ.) & Aria Adli (Univ. of Cologne)

If you are interested in more sonification sounds you can find a previous version here or you can find another sonification project realized by students of music composition and linguistics here.

Paper presented at the Corpus Linguistics 2021 conference on July 13, 2021.

1 Sentence-based sonification

1 sentence corresponds to 1 bar/measure of 1 second length.

1.1 Text genre: academic

1.1.1 Sonificated text (subject: art)

- Aesthetic Appreciation and Spanish Art:

- Insights from Eye-Tracking

- Claire Bailey-Ross claire.bailey-ross@port.ac.uk University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom

- Andrew Beresford a.m.beresford@durham.ac.uk Durham University, United Kingdom

- Daniel Smith daniel.smith2@durham.ac.uk Durham University, United Kingdom

- Claire Warwick c.l.h.warwick@durham.ac.uk Durham University, United Kingdom

- How do people look at and experience art?

- Which elements of specific artworks do they focus on?

- Do museum labels have an impact on how people look at artworks?

- The viewing experience of art is a complex one, involving issues of perception, attention, memory, decision-making, affect, and emotion.

- Thus, the time it takes and the ways of visually exploring an artwork can inform about its relevance, interestingness, and even its aesthetic appeal.

- This paper describes a collaborative pilot project focusing on a unique collection of 17th Century Zurbarán paintings.

- The Jacob cycle at Auckland Castle is the only UK example of a continental collection preserved in situ in purpose-built surroundings.

- While studies of the psychology of art have focused on individual works and distinctions between representative / non-representative topics, no work has been completed on the aesthetic appreciation of collections or of devotional themes.

- In this paper, we report upon the novel insights eye-tracking techniques have provided into the unconscious processes of viewing the unique collection of Zurbarán artworks.

- The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the effects of different written interpretation on the visual exploration of artworks.

- We will discuss the potential implications of these techniques and our understanding of visual behaviours on museum and gallery practice.

- The project brings together established research strengths in Spanish art history, experimental psychology, digital humanities, and museum studies to explore, using eye-tracking techniques, aesthetic reactions to digital representations of the individual Zurbarán artworks as well as the significance of the collection as a whole.

- Our experience of art develops from the interaction of several cognitive and affective processes; the beginning of which is a visual scan of the artwork.

- When regarding an artwork, a viewer gathers information through a series fixations, interspersed by rapid movements of the eye called saccades.

- The direction of saccades is determined by an interaction between the goals of the observer and the physical properties of the different elements of the scene (e.g. colour, texture, brightness etc).

- Importantly, studying eye movements offers an insight that does not depend on the participants’ beliefs, memories or subjective impressions of the artwork.

- Previous eye tracking research has highlighted the potential to transform the ways we understand visual processing in the arts (see for example Brieber 2014; Binderman et al., 2005) and at the same time offers a direct way of studying several important factors of a museum visit (Filippini Fantoni et al., 2013; Heidenreich & Turano 2011; Milekic 2010).

- Zurbarán’s cycle of Jacob and his Sons has been on display in the Long Room at Auckland Castle for over 250 years.

- It is the only cycle to be preserved in purpose-built surroundings in the UK, and one of very few of its kind in the world.

- It has a long history in scholarship (Baron & Beresford 2014), but many key aspects of its production and significance have not yet been fully understood.

- In this study we used eye-tracking in the first stage of exploring audience experience of the extensive Spanish art collections of County Durham, of which the 13 Zurbarán artworks (there are actually only 12 Zurbarán artworks, the 13th Benjamin, is a copy by Arthur Pond) are a key part of, to investigate the ways in which audiences look at Spanish art, how aesthetic experience is evaluated and whether audiences can be encouraged to approach art in different ways.

- This pilot project primarily investigated how participants visually explore artworks and provides new insights into the potential eye-tracking has to transform the ways we understand visual processing in arts and culture and at the same time offer a direct way of studying several important factors of a museum visit, namely to assess the effects of label characteristics on visitor visual behaviour.

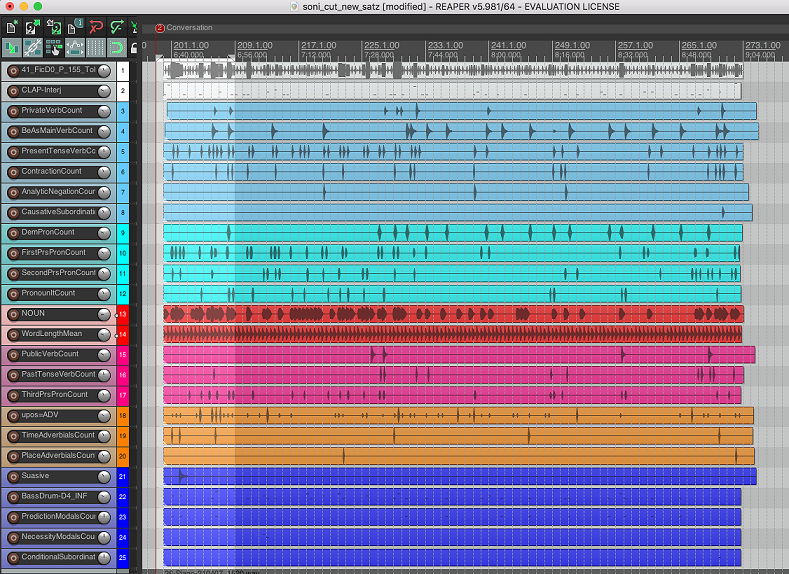

1.1.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features

|

1.2 Text genre: conversation

1.2.1 Sonificated text (subject: atoms)

- Phil: Cool.

- Phil: Alright folks.

- Phil: Well alreet, well alroot, well alright.

- Phil: By now I'm sure you 're wondering about the different things that I have on the table here, but first, I would like to talk to you about these three items.

- Phil: I have here, some ice in a pan, water in this glass, and steam rising from this pot.

- Phil: Now, I would like to ask you, how these three things.

- Phil: Tell me please.

- Phil: How are they all alike.

- Phil: These three things.

- Phil: This ice here in this pan.

- Phil: This water in this glass, and the steam rising from this pot, just yell it out, we are informal here, yes.

- Phil: Correct.

- Phil: They are all forms of water.

- Phil: This ice here of course is water, I told you there was water in this glass, and you have all seen water boil at home, so you are familiar with steam.

- Phil: But now let's try to figure out how they 're different, we'll look at temperature, first.

- Phil: And the temperature of this water here, the ice, is, about uh twenty-four – woo- nineteen degrees.

- Phil: Very cold.

- Phil: The temperature of this w- water here, is sixty-four degrees, the temperature of this steam, is, I know it's hotter than that.

- Phil: Yeah, it's about a hundred and eleven degrees.

- Phil: Okay.

- Phil: Fahrenheit.

- Phil: Okay.

- Phil: Oh, and by the way guys, what do we call something that's hard, like this ice here, or a table, or a rock.

- Phil: We call it a?

- Many: Solid.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: You should g- — you should be a choir.

- Phil: You should go out on the road there, like, yeah.

- Aud: We are.

- Phil: Y- — Oh well, I'm glad to meet you.

- Phil: Please give me your itinerary after the show.

- Phil: Yes.

- Phil: Yes.

- Phil: Of course we call it a sholids.

- Phil: A solid.

- Phil: And a solid has one shape.

- Phil: The shape that it starts out with.

- Phil: And what do we call something that you — that you can splish splash.

- Phil: Take a bath in.

- Phil: Anything wet like soda or milk.

- Many: Liquid.

- Phil: You 're not gon na let me finish, are you?

- Phil: Yes, we call it a?

- Aud: Liquid.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: And a liquid can change its shape, to f- completely fill the bottom of whatever container you put it in.

- Phil: And finally, what do we call something that's loose, and floating around like this steam here?

- Phil: Or a cloud, or the air we breathe, we call it a?

- Many: Gas.

- Phil: Correct.

- Phil: A gas.

- Phil: And a gas completely fills whatever shape container you put it in.

- Phil: And so, how do you get water to change, from a solid, to a liquid, to a gas, and back and forth?

- Aud: Add energy.

- Phil: Woo.

- Phil: I like the way he expressed that.

- Phil: Never before have I heard it, add or subtract energy, or, heat, change the temperature, basically.

- Phil: Correct?

- Phil: Alright.

- Phil: Well folks, now I'm going to show you something else that happens when you change the temperature, and that's where these balloons come in.

- Phil: I have here a number of balloons, but, l- let's see how many of these balloons, I can fit, into this little itty-bitty container here.

- Phil: Well, everybody count together.

- Phil: This would be ...

- Aud: There's a- in there.

- Phil: You think, well, okay, w- th- th-, I'm glad I never saw d- Citizen Kane with you.

- Phil: Rosebud is a sled.

- Phil: Okay.

- Phil: Well, let's all count together folks, that was?

- Aud1: One.

- Aud2: One.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: One balloon going into the little container here.

- Phil: And this would be ...

- Many: Two.

- Phil: Two.

- Phil: Very good counting there.

- Phil: Two.

- Phil: Excellent.

- Phil: Two balloons going into the little container here.

- Phil: Ah, they 're not fitting in so easily.

- Phil: Oh no.

- Phil: So hopefully I can fit all balloons into this little container here.

- Phil: Oh stop guessing at what this is.

- Phil: Let's have some suspense here.

- Phil: Come on.

- Phil: Alright.

- Phil: And this would be?

- Many: Three.

- Phil: Three.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: Three balloons going onto the the little container there.

- Phil: Three balloons.

- Phil: Three, yes, the balloon trinity.

- Phil: And now, this would be?

- Aud1: Eight.

- Aud3: Four.

- Phil: Four.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: At first he was confused, but then he figured it out.

- Phil: Everybody tell him what this is, it's ...

- Phil: Seven.

- Phil: It's four.

- Phil: Boy you people didn't watch enough Sesame Street as a child.

- Phil: This would be?

- Many: Five.

- Phil: Thank you very much, yes.

- Phil: Five swollen balloons.

- Phil: In.

- Phil: In.

- Phil: Down.

- Phil: Down.

- Phil: Ah, ah.

- Phil: Okay.

- Phil: And this would be?

- Many: Six.

- Phil: Six, good.

- Phil: And let's do this uh, let's add some complexities to this here, let's do it in another language.

- Phil: In Spanish it would be?

- Aud1: Ocho.

- Aud2: Seis.

- Phil: S- seis.

- Phil: N- ocho.

- Phil: Oh my gosh.

- Phil: I'm afraid for our nation.

- Phil: Okay, well, and this would be?

- Aud: Siete.

- Phil: Thank you.

- Phil: Seven.

- Phil: Right?

- Phil: Seven.

- Phil: Okay.

- Phil: And finally, this would be?

- Aud1: Eight.

- Aud2: Ocho.

- Phil: Eight, or ocho in Spanish, and uh huit in French, thank you very much.

- Phil: I thought you were telling me your breakfast.

- Phil: What you had for b- — But no, huit.

- Phil: Very good.

- Phil: Oh my gosh, eight balloons into this little container here, I bet you 're wondering r- how that happened.

- Aud1: You popped two.

- Aud2: There's a hole in it.

- Phil: Well, there's a hole, no, if you 're thinking there's a hole, think again.

- Phil: Because, there's no hole in the counter at all.

- Aud1: Pull em out.

- Aud2: You slowed down the molecules,

- Phil: Well – la duh dah dih duh duh, you 're getting a little ahead of me son.

- Phil: Let's all figure it out together.

1.2.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features

|

1.3 Text genre: interview

1.3.1 Sonificated text (subject: ants)

- Biologist Nick Bos tells Wikinews about 'self-medicating' ants

- Tuesday, September 1, 2015

- Formica fusca, from file.

- Image: Mathias Krumbholz.

- Nick Bos, of the University of Helsinki, studies "the amazing adaptations social insects have evolved in order to fight the extreme parasite pressure they experience".

- In a recently-accepted Evolution paper Bos and colleagues describe ants appearing to self-medicate.

- "I have no doubt that as time goes on, there will be more and more cases documented"

- The team used Formica fusca, an ant species that can form thousand-strong colonies.

- This common black ant eats other insects, and also aphid honeydew.

- It often nests in tree stumps or under rocks and foraging workers can sometimes be spotted climbing trees.

- Some ants were infected with Beauveria bassiana, a fungus.

- Infected ants chose food laced with toxic hydrogen peroxide, whereas healthy ants avoided it.

- Hydrogen peroxide reduced infected ant fatalities by 15%, and the ants varied their intake depending upon how high the peroxide concentration was.

- In the wild, Formica fusca can encounter similar chemicals in aphids and dead ants.

- The Independent reported self-medicating ants a first among insects.

- Bos obtained his doctorate from the University of Copenhagen.

- He began postdoctoral research at Helsinki in 2012.

- He also runs the AntyScience blog.

- The blog aims to help address "a gap between scientists and 'the general public'."

- The name is a pun referencing ants, its primary topic, science, and "non-scientific" jargon-free communication.

- He now discusses his work with Wikinews.

- Beauveria bassiana on a cicada in Bolivia.

- Image: Danny Newman.

- What first attracted you to researching ants?

- Me and a studymate were keeping a lot of animals during our studies, from beetles, to butterflies and mantids, to ants.

- We had the ants in an observation nest, and I could just look at them for hours, watching them go about.

- This was in my third year of Biology study I think.

- After a while I needed to start thinking about an internship for my M.Sc. studies, and decided to write a couple of professors.

- I ended up going to the Centre for Social Evolution at the University of Copenhagen where I did a project on learning in Ants under supervision of Prof. Patrizia d'Ettorre.

- I liked it so much there I ended up doing a PhD and I've been working on social insects ever since.

- What methods and equipment were used for this investigation?

- This is a fun one.

- I try to work on a very low budget, and like to build most of the experimental setups myself (we actually have equipment in the lab nicknamed the 'Nickinator', 'i-Nick' and the 'Nicktendo64').

- There's not that much money in fundamental science at the moment, so I try to cut the costs wherever possible.

- We collected wild colonies of Formica fusca by searching through old tree-trunks in old logging sites in southern Finland.

- We then housed the ants in nests I made using Y-tong [aerated concrete].

- It's very soft stone that you can easily carve.

- We carved out little squares for the ants to live in (covered with old CD covers to prevent them escaping!).

- We then drilled a tunnel to a pot (the foraging arena), where the ants got the choice between the food with medicine and the food without.

- We infected the ants by preparing a solution of the fungus Beauveria bassiana.

- Afterwards, each ant was dipped in the solution for a couple of seconds, dried on a cloth and put in the nest.

- After exposing the ants to the fungus, we took pictures of each foraging arena three times per day, and counted how many ants were present on each food-source.

- Example of aerated concrete, which provided a home for the subjects.

- Image: Marco Bernardini.

- This gave us the data that ants choose more medicine after they have been infected.

- The result that healthy ants die sooner when ingesting ROS [Reactive Oxygen Species, the group of chemicals that includes hydrogen peroxide] but infected ants die less was obtained in another way (as you have to 'force feed' the ROS, as healthy ants, when given the choice, ignore that food-source.)

- For this we basically put colonies on a diet of either food with medicine or without for a while.

- And afterwards either infected them or not. Then for about two weeks we count every day how many ants died.

- This gives us the data to do a so-called survival analysis.

- We measured the ROS-concentration in the bodies of ants after they ingested the food with the medicine using a spectrophotometer.

- By adding certain chemicals, the ROS can be measured using the emission of light of a certain wave-length.

- The detrimental effect of ROS on spores was easy to measure.

- We mixed different concentrations of ROS with the spores, plated them out on petridishes with an agar-solution where fungus can grow on.

- A day after, we counted how many spores were still alive.

- How reliable do you consider your results to be?

- The results we got are very reliable.

- We had a lot of colonies containing a lot of ants, and wherever possible we conducted the experiment blind.

- This means the experimenter doesn't know which ants belong to which treatment, so it's impossible to influence the results with 'observer bias'.

- However, of course this is proof in just one species.

- It is hard to extrapolate to other ants, as different species lead very different lives.

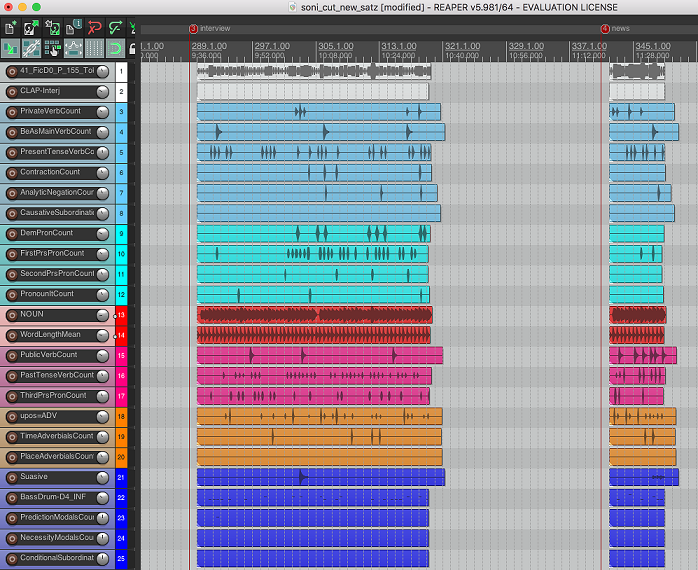

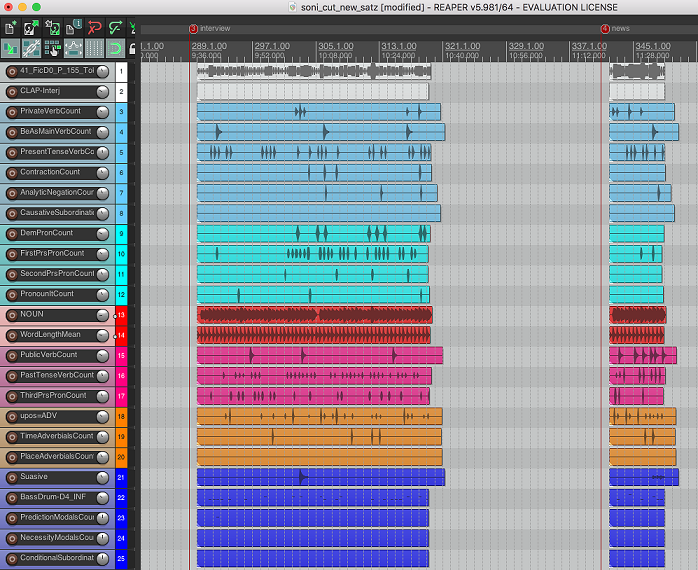

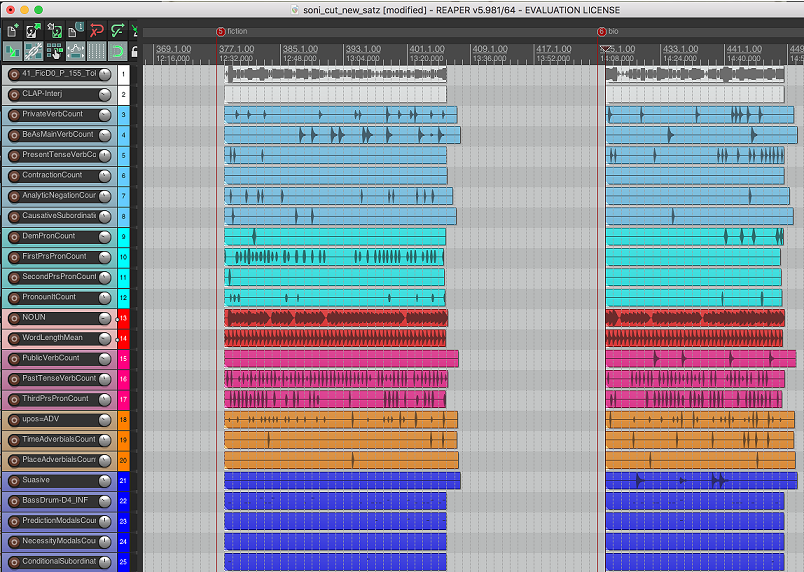

1.3.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features (see left part)

|

1.4 Text genre: news

1.4.1 Sonificated text (subject: asylum)

- Over 900 asylum seekers rescued off Indonesian coast

- Monday, May 18, 2015

- On Friday, fishermen rescued over 700 asylum seekers whose boat sank, and the Indonesian Navy reportedly saved 200 more after they were found swimming along the coast of Aceh, Indonesia.

- Major general Fuad Basya, spokesman for the Indonesian military, said fisherman first noticed the people and a warship was deployed to retrieve them.

- The rescued members included Bangladeshis and Rohingya, a stateless minority of Muslims from Myanmar.

- Myanmar is mainly Buddhist and the United Nations rates the Rohingya among the world's most persecuted groups.

- According to ABC News, Basya also believes the asylum seekers found in the water may have left the boat on purpose to be rescued to avoid being sent away from Indonesia waters.

- Malaysia and Indonesia have maintained a policy of turning away boats of migrants which, according to AFP, the Untied Nations and United States have both criticised.

- One Rohingya, Muhammad Amin, the first boat rescued on Friday was turned around twice, toward Malaysia by Indonesian navy and then toward Indonesia by Malaysian navy.

- Discussing his concern in a public statement, Malaysia's Prime Minister, Najib Razak said, "We are in contact with all relevant parties, with whom we share the desire to find a solution to this crisis".

- Thailand has recently cracked down on human trafficking, which has affected the routes by which people-smugglers transport migrants.

- The US State Department said John Kerry, the Secretary of State, contacted Thailand's foreign minister over temporary housing for the Rohingya out at sea.

- Jeff Rathke, the State Department Spokesperson, said, "We urge the governments of the region to work together quickly, first and foremost, to save the lives of migrants now at sea who are in need of an immediate rescue effort".

- Rathke also asked the governments of South East Asia not to turn away boats of people seeking asylum.

- Estimates suggest 8000 migrants may be currently at sea in the region.

1.4.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features (see right part)

|

1.5 Text genre: fiction

1.5.1 Sonificated text (subject: beast)

- The Beast

- I was thirteen.

- It was spring, the barren time in March when you can not be sure if it is really warmer, but you are so desperate for change that you tell yourself the mud at the edge of the sidewalk is different from winter mud and you are sure that the smell of wet soil has suddenly a bit of the scent of summer rains, of grass and drowned earthworms.

- And it has, because it is spring and inside the ground something is stirring.

- I was wearing a yellow linen dress which my mother had picked out and which I therefore disliked although I knew it flattered me.

- My shoes were white and I was concentrating on keeping them out of the mud.

- My father and I were going to mass — my mother did not go; she was Protestant.

- My father put his hand on top of my hair, his palm on my head, and I could feel the bone of my skull and my skin and his hot palm, so dry and strong.

- When I was a little girl, he did that often, and called me Muscles.

- He had not called me Muscles or put his hand on my head for a long time.

- I could not help arching my back a little, I wanted to push against his hand like a cat but the instinct that comes with being thirteen, the half-understood caution that makes a girl timid, or wild, the shyness told me to just walk.

- I wanted to feel the rough edge of the pocket of his coat against my cheek, but I was too tall.

- I wanted to be seven again, and safe.

- But I still wanted to push against his hand and put my hand in his pocket and steal the leather palmed glove, that secret animal.

- Instead I went into the church, took a Bulletin, dipped my finger in Holy Water and genuflected.

- The inside of the church smelled like damp wood and furniture polish, not alive at all.

- My father took off his coat and draped it over the edge of the pew and when I came back from communion I stole his glove.

- The paper taste of the wafer was still in my mouth and I took a deep breath of the leather.

- It smelled like March.

- We walked back through the school because it was drizzling, my father tall in his navy suit and my shoes going click on the linoleum.

- There were two classes of each grade, starting at the sixth and going down to the first.

- The hall ended in a T and we went left through the gym, walked underneath the bleachers and stood next to the side door, waiting for the rain to stop.

- It was dark under the bleachers.

- My father was a young man, thirty-five, younger because he liked to be outside, to play softball on Saturday and to take my mother and me camping on vacation.

- He stood rocked back on his heels with his coat thrown over his shoulders and his hands in his pockets.

- I thought of bacon and eggs, toast with peach jam out of the jar.

- I was so hungry.

- The space under the bleachers was secret and dark.

- There were things in the shadows; a metal pail, a mop, rags.

- Next to the door was a tall wrought-iron candle holder — the kind that stood at either end of the altar.

- There was no holder and the end was jagged.

- On the floor was a wrapper from a French Chew.

- They were sold at eighth-grade basketball games on Friday nights.

- The light from the door made the shadows under the bleachers darker, the long space stretched far away.

- I heard the rain and the faint rustle of paper and smelled damp concrete.

- I did not go near my father but kept my hand in my pocket, feeling the soft leather glove.

- There was a rustling on the concrete and the drizzle of soft rain.

- I wondered if anyone ever went back under the bleachers, if there were crickets or mice there.

- The rustling might have been mice.

- I wished the rain would stop.

- I wanted to go home.

- I made noises with my heels but they were too loud so I stopped.

- Something else clicked and I tried to see what it was but couldn’t see anything.

- It wasn’t as loud as my heels.

- My father cleared his throat, looking out the door.

- I imagined a man down there in the dark, an escaped convict or a madman.

- It had nearly stopped raining.

- In fifteen minutes we would be home and my mother would fry eggs.

- I heard a noise like paper.

- My father heard it, too, but he pretended not to, at least he didn’t turn his head.

- And there was a heavier sound, a rasp, like a box pulled over concrete.

- I looked at my father but he didn’t turn his head.

- I wished he would turn his head.

- There was a click again and the rustle, and I could not think of what it could be.

- I had no explanation for the particular combination of sounds.

- No doubt there was, some two things that happened to be making noises at the same time.

- Once in a fever I heard thousands of birds outside my window and I was terrified that they would fling themselves through the glass and attack me, but it was only the rain on the eaves.

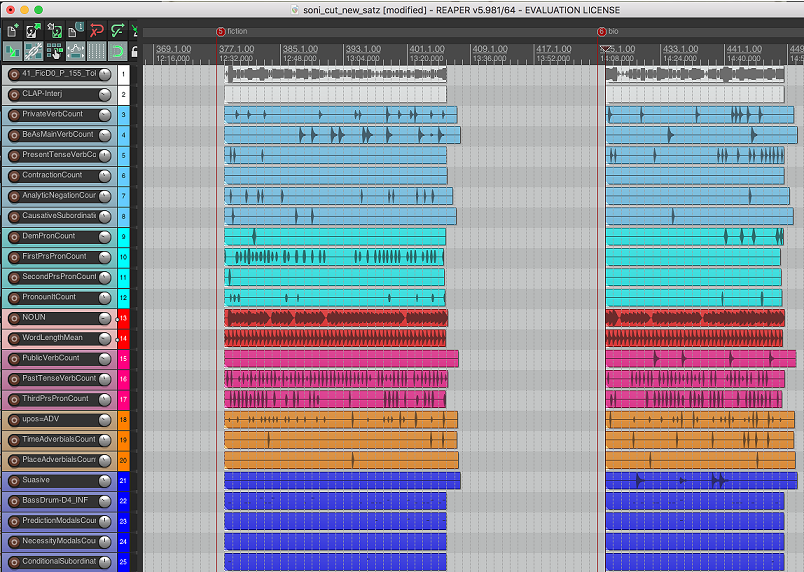

1.5.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features (see left part)

|

1.6 Text genre: biography

1.6.1 Sonificated text (subject: Daniel Bernoulli)

- Daniel Bernoulli

- Daniel Bernoulli FRS (German pronunciation: [bɛʁˈnʊli]; 8 February 1700 – 17 March 1782) was a Swiss mathematician and physicist and was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family.

- He is particularly remembered for his applications of mathematics to mechanics, especially fluid mechanics, and for his pioneering work in probability and statistics.

- His name is commemorated in the Bernoulli's principle, a particular example of the conservation of energy, which describes the mathematics of the mechanism underlying the operation of two important technologies of the 20th century: the carburetor and the airplane wing.

- Daniel Bernoulli

- Early life

- Frontpage of Hydrodynamica (1738)

- Daniel Bernoulli was born in Groningen, in the Netherlands, into a family of distinguished mathematicians.

- The Bernoulli family came originally from Antwerp, at that time in the Spanish Netherlands, but emigrated to escape the Spanish persecution of the Huguenots.

- After a brief period in Frankfurt the family moved to Basel, in Switzerland.

- Daniel was a son of Johann Bernoulli (one of the "early developers" of calculus) and a nephew of Jacob Bernoulli (who" was the first to discover the theory of probability").

- He had two brothers, Niklaus and Johann II.

- Daniel Bernoulli was described by W. W. Rouse Ball as "by far the ablest of the younger Bernoullis".

- He is said to have had a bad relationship with his father.

- Upon both of them entering and tying for first place in a scientific contest at the University of Paris, Johann, unable to bear the "shame" of being compared Daniel's equal, banned Daniel from his house.

- Johann Bernoulli also plagiarized some key ideas from Daniel's book Hydrodynamica in his own book Hydraulica which he backdated to before Hydrodynamica.

- Despite Daniel's attempts at reconciliation, his father carried the grudge until his death.

- Around schooling age, his father, Johann, encouraged him to study business, there being poor rewards awaiting a mathematician.

- However, Daniel refused, because he wanted to study mathematics.

- He later gave in to his father's wish and studied business.

- His father then asked him to study in medicine, and Daniel agreed under the condition that his father would teach him mathematics privately, which they continued for some time.

- Daniel studied medicine at Basel, Heidelberg, and Strasbourg, and earned a PhD in anatomy and botany in 1721.

- He was a contemporary and close friend of Leonhard Euler.

- He went to St. Petersburg in 1724 as professor of mathematics, but was very unhappy there, and a temporary illness in 1733 gave him an excuse for leaving St. Petersburg.

- He returned to the University of Basel, where he successively held the chairs of medicine, metaphysics, and natural philosophy until his death.

- In May, 1750 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

- Mathematical work

- His earliest mathematical work was the Exercitationes (Mathematical Exercises), published in 1724 with the help of Goldbach.

- Two years later he pointed out for the first time the frequent desirability of resolving a compound motion into motions of translation and motion of rotation.

- His chief work is Hydrodynamica, published in 1738;

- it resembles Joseph Louis Lagrange's Mécanique Analytique in being arranged so that all the results are consequences of a single principle, namely, conservation of energy.

- This was followed by a memoir on the theory of the tides, to which, conjointly with the memoirs by Euler and Colin Maclaurin, a prize was awarded by the French Academy: these three memoirs contain all that was done on this subject between the publication of Isaac Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica and the investigations of Pierre-Simon Laplace.

- Bernoulli also wrote a large number of papers on various mechanical questions, especially on problems connected with vibrating strings, and the solutions given by Brook Taylor and by Jean le Rond d'Alembert.

- Together Bernoulli and Euler tried to discover more about the flow of fluids.

- In particular, they wanted to know about the relationship between the speed at which blood flows and its pressure.

- To investigate this, Daniel experimented by puncturing the wall of a pipe with a small open ended straw and noted that the height to which the fluid rose up the straw was related to fluid's pressure in the pipe.

- Soon physicians all over Europe were measuring patients' blood pressure by sticking point-ended glass tubes directly into their arteries.

- It was not until about 170 years later, in 1896 that an Italian doctor discovered a less painful method which is still in use today.

- However, Bernoulli's method of measuring pressure is still used today in modern aircraft to measure the speed of the air passing the plane; that is its air speed.

- Taking his discoveries further, Daniel Bernoulli now returned to his earlier work on Conservation of Energy.

- It was known that a moving body exchanges its kinetic energy for potential energy when it gains height.

- Daniel realised that in a similar way, a moving fluid exchanges its kinetic energy for pressure.

- Mathematically this law is now written: ½ ρ u 2 + P = constant where P is pressure, ρ is the density of the fluid and u is its velocity.

- A consequence of this law is that if the velocity increases then the pressure falls.

- This is exploited by the wing of an aeroplane which is designed to create an area above its surface where the air velocity increases.

- The pressure in this area is lower than that under the wing, so the wing is pushed upwards by the relatively higher pressure under the wing.

1.6.2 Multitrack DAW visualization of sonificated linguistic features (see right part)

|

2 Document-based sonification

1 document corresponds to 1 bar/measure of 4.5 seconds length.

All documents belonging to a text genre in the GUM corpus are sonificated.

2.1 Text genre: academic |

2.5 Text genre: fiction |

2.9 Text genre: vlog |

2.2 Text genre: conversation |

2.6 Text genre: biography |

2.10 Text genre: voyage |

2.3 Text genre: interview |

2.7 Text genre: speech |

2.11 Text genre: whow |

2.4 Text genre: news |

2.8 Text genre: textbook |

3 Decomposed sonificated linguistic features/sounds

3.1 Selection of linguistic features on Biber’s (1988: 89) factor 1

Specialized verb classes according to Biber 1888

3.1.1 Private verbs

"Private verbs express intellectual states (e.g., believe) or nonobservable intellectual acts (e.g., discover); this class corresponds to the 'verbs of cognition' used in other studies.

(e.g., anticipate, assume, believe, conclude, decide, demonstrate, determine, discover, doubt, estimate, fear, feel, find, forget, guess, hear, hope, imagine, imply, indicate, infer, know, learn, mean, notice, prove, realize, recognize, remember, reveal, see, show, suppose, think, understand).

This class of verbs is taken from Quirk et al. (1985:1181-2)."

(Biber 1988: 242)

3.1.2 Contractions

"(1) all contractions on pronouns

(2) all contractions on auxiliary forms (negation)

(3) 's suffixed on nouns is analyzed separately (to exclude possessive forms):

N's + V/AUX/ADV+V/ADV+AUX/DET/POSSPRO/

PREP/ADJ+CL-P/ADJ+TS

Contractions are the most frequently cited example of reduced surface form. Except for certain types of fiction, they are dispreferred in formal, edited writing; linguists have traditionally explained their frequent use in conversation as being a consequence of fast and easy production. Finegan and Biber (1986a), however, find that contractions are distributed as a cline: used most frequently in conversation; least frequently in academic prose; and with intermediate frequencies in broadcast, public speeches, and press reportage. Biber (1987) finds that contractions are more frequent in American writing than in British writing, apparently because of greater attention to grammatical prescriptions by British writers. Chafe and Danielewicz (1986) also find that there is no absolute difference between speech and writing in the use of contractions. Thus, the use of contractions seems to be tied to appropriateness considerations as much as to the differing production circumstances of speech and writing. Other references include: Marckworth and Baker (1974), Chafe (1985), and Biber (1986a)."

(Biber 1988: 243)

3.1.5 Analytic negation

"There is twice as much negation overall in speech as in writing, a distribution that Tottie (1981, 1982, 1983b) attributes to the greater frequency of repetitions, denials, rejections, questions, and mental verbs in speech. Tottie (1983a) distinguishes between synthetic and analytic negation. Synthetic negation is more literary, and seemingly more integrated; analytic negation is more colloquial and seems to be more fragmented.

66. synthetic negation

(a) no + QUANT/ADJ/N

(b) neither, nor

(excludes no as a response)

67. analytic negation: not

(also contracted forms)"

(Biber 1988: 245)

3.1.6 Demonstrative pronouns

"(a) thatl this I these I those + V/AUX/CL-P/TS/WHP/W

(where that is not a relative pronoun)

(b) that's

(c) Tt + that

(that in this last context was edited by hand to distinguish among demonstrative pronouns, relative pronouns, complementizers, etc.)

Demonstrative pronouns can refer to an entity outside the text, an exophoric referent, or to a previous referent in the text itself. In the latter case, it can refer to a specific nominal entity or to an inexplicit, often abstract, concept (e.g., this shows . . .). Chafe (1985; Chafe and Danielewicz 1986) characterizes those demonstrative pronouns that are used without nominal referents as errors typically found in speech due to faster production and the lack of editing. Demonstrative pronouns have also been used for register comparisons by Carroll (1960) and Hu (1984)."

(Biber 1988: 226)

3.1.8 Pronoun It

"It is the most generalized pronoun, since it can stand for referents ranging from animate beings to abstract concepts. This pronoun can be substituted for nouns, phrases, or whole clauses. Chafe and Danielewicz (1986) and Biber (1986a) treat a frequent use of this pronoun as marking a relatively inexplicit lexical content due to strict time constraints and a non-informational focus. Kroch and Hindle (1982) associate greater generalized pronoun use with the limited amounts of information that can be produced and comprehended in typical spoken situations."

(Biber 1988: 225f)

3.1.9 BE as main verb

"Be as main verb is used for register comparisons by Carroll (1960) and Marckworth and Baker (1974).

BE + DET/POSSPRO/TITLE/PREP/ADJ"

(Biber 1988: 229)

3.1.10 Causative subordination: because

"Because is the only subordinator to function unambiguously as a causative adverbial. Other forms, such as as, for, and since, can have a range of functions, including causative. Most researchers find more causative adverbials in speech (Beaman 1984; Tottie 1986), although the functional reasons for this distribution are not clear. Tottie (1986) and Altenberg (1984) both provide detailed analyses of these subordination constructions. For example, Tottie notes that while there is more causative subordination overall in speech, the form as is used as a causative subordinator more in writing. Other references: Smith and Frawley (1983), Schiffrin (1985b)."

(Biber 1988: 236)

3.1.12 Word length

"mean length of the words in a text, in orthographic letters" (Biber 1988: 239)

3.1.1 Private verbs |

3.1.10 Causative subordination |

3.1.19 Place adverbs |

3.1.2 Contractions |

3.1.11 Nouns |

3.1.20 Time adverbs |

3.1.3 Present tense verbs |

3.1.12 Word length |

3.1.21 Conditional |

3.1.4 2nd person pronouns |

3.1.13 Token pls |

3.1.22 Infinitives |

3.1.5 Analytic negation |

3.1.14 Interjection clap |

3.1.23 Necessity |

3.1.6 Demonstrative pronouns |

3.1.15 3rd person pronouns |

3.1.24 Prediction |

3.1.7 1st person pronouns |

3.1.16 Past tense |

3.1.25 Suasive Verbs |

3.1.8 Pronoun It |

3.1.17 Public verb |

|

3.1.9 BE as main verb |

3.1.18 Adverbs |

3.5 Sonificated features not included in Biber’s analysis

3.5.1 Mean utterance length (number of tokens) |

3.5.2 Interjections |